Here in Central Oregon, we can’t look outside without noting the geological forces that have shaped the landscape around us. From our impressive Cascade Mountain range to our vast lava flows, interesting geology is on a display all around us. This month, we are profiling an American geologist for our Women of Discovery spotlight, Marie Tharp (1920-2006). Known for her study of the sea, rather than the mountains, her work is fascinating all the same.

Hailing from Michigan, Tharp spent much of her childhood moving around the U.S. for her father’s job. She first showed an interest in science when she attended college at Ohio University, where she “discovered her love” of geology as a discipline. She however, ended up pursuing a liberal arts degree in English and music. As World War II advanced, a need for petroleum spurred offers of accelerated degrees in geology among U.S. colleges and universities. Tharp took advantage of the offer, attending grad school at University of Michigan, and her career as a geologist was launched.

Hailing from Michigan, Tharp spent much of her childhood moving around the U.S. for her father’s job. She first showed an interest in science when she attended college at Ohio University, where she “discovered her love” of geology as a discipline. She however, ended up pursuing a liberal arts degree in English and music. As World War II advanced, a need for petroleum spurred offers of accelerated degrees in geology among U.S. colleges and universities. Tharp took advantage of the offer, attending grad school at University of Michigan, and her career as a geologist was launched.

Her first job at an oil company didn’t allow women to work in the field, and she tired quickly of office work so she enrolled at University of Tulsa for another advanced degree. Her next job was as a research assistant at Columbia University’s Lamont Geological Observatory; she was one of the first women to work at the organization.

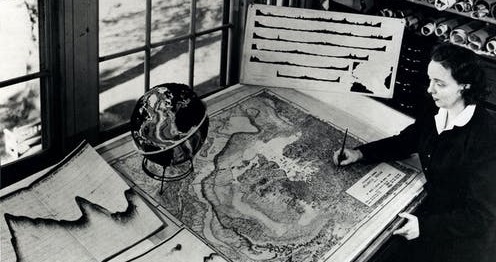

Some say it was her “unconventional education” that led her to interest in studying the structure of the ocean floor – the work for which she is most well-known. In the 1950s, she used a number of different data sources, including information and photography captured on expeditions into the Atlantic Ocean in order to graph the seafloor and topography. Because of her gender, she could not conduct research from a ship herself and relied on her research partner Bruce Heezen to bring back much of the data she used in her work.

Her discoveries showed the diverse structure of the ocean floor, previously thought to be flat, as well as the presence of a Mid-Atlantic Ridge. This ridge was significant because, when overlaid with earthquake data, it helped to prove the theories of plate tectonics and continental drift, which were controversial at the time.

Tharp was honored for her work with several awards including the National Geographic Society’s Hubbard Medal and the Society of Woman Geographers Outstanding Achievement Award, among others. A fellowship in her name was set up for women to work with researchers at Columbia University. And now, she has a street named after her in our Bend, Oregon neighborhood of Discovery West!